“Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the cosmos. Polka dots are a way to infinity. When we obliterate nature and our bodies with polka dots, we become part of the unity of our environment.”

Yayoi Kusama is a Japanese contemporary artist who works in sculpture, painting, installation, performance, film, fashion, poetry, fiction, and other arts. She works in conceptual art, with aspects of feminism, minimalism, surrealism, Art Brut, pop art, and abstract expressionism.

Embed from Getty ImagesShe exploded into international fame a few years ago with her Infinity Rooms exhibitions and eye-catching polka dot style. However, she’s been a highly influential figure in the art world since the 1960s—her influence was overlooked because of her race and gender. A tale as old as time.

Kusama was born on March 22, 1929 in Matsumoto, Nagano. She is 91 going on 92; patrons still fall in line—especially because she is one of the most important living artists to come out of Japan.

When she was young, she had a fair amount of family issues because her mother assumed that her father was having an affair and forced Kusama to spy on him. This eventually caused her to claim to experience visual hallucinations—she regularly saw dense concentrations of lights and circles, which prompted her to begin painting dot patterns that became the inspiration for her iconic polka dot work and fashion. It also led to a life-long and multifaceted obsession with sex. She found it both fascinating and disgusting and produced numerous phallic artworks as a result of this.

Embed from Getty ImagesKusama tells a story of how when she was a little girl she had a hallucination that freaked her out—she was in a field of flowers that started talking to her. The heads of flowers transformed into dots that went on as far as she could see, and she felt as if she was disappearing, or “self-obliterating,” into this field of endless dots.

In 1939, at the age of 10, she created the drawing “Untitled,” which showed an image of her mother’s face against a background all covered in polka dots. The polka dots represent not only what she saw but also the universe as a whole and its infinite nature. By adding marks and dots to her art, she feels as if she is making them, and herself, melt into and become part of the bigger universe. This piece was a foreshadow into her future as an artist, with her career primarily focusing on her lifelong exploration into herself, an obsession with polka dots, and the various ways she could represent self-obliteration.

Embed from Getty Images Embed from Getty ImagesGrowing up, her mother was not supportive of Kusama becoming an artist. She would rip up her works of art and steal them away from her. But this did not deter her. Kusama’s mother wanted her to become a traditional and conventional Japanese housewife—a role that she was not suited for. She strongly persevered and did not let go of her artistic pursuits.

With the outbreak of WWII, Kusama was conscripted to work for 12 hours a day in a parachute factory. Despite this exhausting task, she still found the time and resources to produce art. She began publicly exhibiting her work in group exhibitions throughout her teens, and in 1948, she convinced her parents to let her go to Kyoto to study nihonga. She was trained at the Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts but became frustrated with the distinctively traditional Japanese style of nihonga and turned to American abstract expressionism for inspiration. Kusama’s great ambition and talent were recognized when she began staging solo shows in her hometown in the early 1950s. In 1955, she started a written dialogue with the American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and decided that she wanted to go to the U.S.

“My constant battle with art began when I was still a child. But my destiny was decided when I made up my mind to leave Japan and journey to America.”

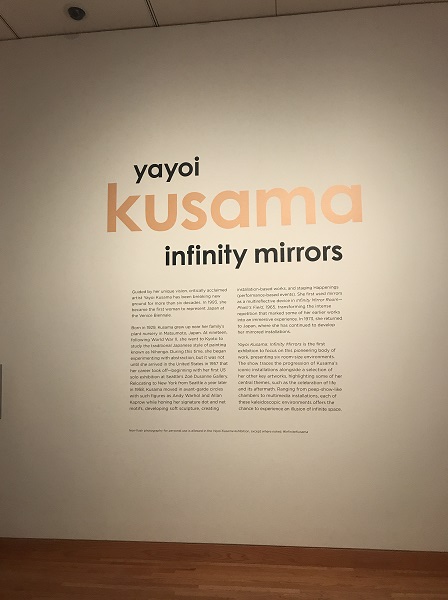

In 1957, Yayoi Kusama entered the U.S. via my hometown, Seattle. On her visa application, she officially declared her reason for entry as exhibiting art in Seattle. Her first show in the U.S. was a solo show at the Zoë Dusanne Gallery. It included a group of around 20 watercolors and pastels selected from the 200 works that Kusama brought with her from Japan. She began her international career in Seattle, which is probably why Seattle was selected as one of the U.S. cities to host her renowned “Infinity Rooms” exhibit.

In a 1957 Seattle Times feature on her solo show, Louis Guzzo pointed out that, “several of the smaller works are beautiful, but one must study them closely to realize the intricacies of their microscopic worlds.” Kusama asserts that all of her work is part of a whole, a whole that we are all a part of in her concept of the infinite.

After staying for a year in Seattle, Kusama moved on to New York City. In the 1960s she became a key figure in the New York avant-garde movements but it wasn’t until after her departure in the 1970s when her work was recognized with the credit it deserved.

During her early years in the States, Kusama emphasized her foreignness by dressing in formal Japanese kimono she had brought from Japan for her private art viewings. In 1966, she made her slide work, Walking Piece, which recorded the artist walking through desolate NYC streets in a bright pink floral kimono. She applied the kimono as a symbol of otherness and intentionally positioned herself as a vivid outsider in the midst of an unfriendly and foreign city.

Despite her broken English, she came into contact with famous artists like Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, and Joseph Cornell. She was welcomed as an outsider but was sometimes refused entrance to galleries or exhibits because of her race and gender. As a female Japanese artist trying to create new and convention-defying art in this white male-dominated society, she was a big influence on many famous artists—but was discredited and ripped off by the same men. Having been taken advantage of by numerous famous male artists, she became depressed and attempted suicide.

Yayoi Kusama returned to Japan in 1973 and underwent treatment for depersonalization syndrome. In 1977, she admitted herself into a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo and continues to live there today. She has a studio in close proximity to the hospital where she continues to create every day. In 1993, she was selected to represent Japan in the Venice Biennale and has had a large number of solo exhibitions around the world, including the Serpentine Gallery in London, the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There’s also an entire museum in Tokyo dedicated to her, called the Yayoi Kusama Museum.

Embed from Getty Images Embed from Getty ImagesKusama’s work and identity as an artist have always been intertwined—she is often seen photographed together with her art. Through an autobiographical look at her psychology and mental illness, she disassembles her identity and frees herself through her art. She continues to create pieces of “self-obliteration” by using polka dots to unify both herself and ourselves with the universe. Her Infinity Rooms exhibition creates this environment of self-obliteration for us by surrounding us in mirrored rooms filled with flashing colored LED lights. The lights reflect endlessly in the mirrors, creating an engulfing sense of infinity and the feeling of becoming one with the universe—the feeling of becoming one with Yayoi Kusama.

A note: I was lucky enough to attend the Infinity Rooms exhibit in Seattle and have posted pictures from it below.

Sources: “5 Influential Japanese Women Breaking Stereotypes”; “The Self-Obliteration of Yayoi Kusama”; “Iconic Faces: 5 Renowned Japanese Women You Should Know”; “Who is Yayoi Kusama?”; “Kusama’s Full Circle”; “Yayoi Kusama”; “Kusama and Fashion”; “Yayoi Kusama’s Early Years”

Infinity Mirrors. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Infinity Mirrored Room—Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity. 2009. Wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, LEDs, and aluminum.Collection of the artist. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field. 1965/2016. Stuffed cotton, board, and mirrors. Collection of the artist. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Infinity Mirrored Room—Love Forever. 1966/1994. Wood, mirrors, metal, and lightbulbs. Collection of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Dots Obsession—Love Transformed into Dots. 2007, installed 2017. Vinyl balloons, balloon dome with mirror room, peep-in mirror dome, and video projection. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

We were given sheets of polka dot stickers to transform a white furnished room into our own obliteration space. We attended the exhibition at the beginning of its opening, so the room still had a lot of white space. By the closing of the exhibition, the entire room was obliterated in colorful polka dots. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

My mother enjoying the experience. Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Photo by Malia Ogawa.

Some people got creative and attached their polka dots to other polka dots, like on this clock. Photo by Malia Ogawa.