On the advent of the twentieth century, an exquisitely talented Japanese geisha arrived in the U.S. and took the West by storm. Traveling on to Europe, she was destined to leave her mark on each city and every heart fortunate enough to be graced by her presence. Japan, and its enchanting representative, had arrived.

Sada Yacco by Alfredo Müller, 1899-1900

Sadayakko Kawakami (commonly known as Sada Yacco) was born on July 18, 1871, the youngest of 12 children. At the early age of four, she was sent to work in the Hamada geisha house, located in the Yoshicho district of Tokyo. Three years later, her father died and the proprietress of the Hamada house adopted Sada as her heir.

She debuted at the age of 12 as an o-shaku (an apprentice geisha), and received her first geisha name. She was given the name Ko-yakko, or Little Yakko. She was sent to a Shinto priest to learn how to read and write, which was revolutionary at the time because women’s education was only just beginning. She took secret lessons in judo and learned how to ride horses and play billiards.

In 1886, her mizuage was sold to Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi at the age of 15. Her coming-of-age ceremony gave her the name Yakko, and the prestige of her patron increased her popularity at teahouses. He remained her patron, and she his mistress, for three years.

She discovered a passion for acting through the entertainment world of the geisha. Geisha performed music and dance of the same genre as kabuki, including dance solos from kabuki plays—but only for private and exclusive customers. Yakko much preferred the exciting male roles in these performances, with their dramatic posing and fight scenes, over the coy women’s parts.

Yakko married an actor named Otojiro Kawakami in October 1893. She had met him during a private performance by his troupe for the prime minister and a select few geisha. His flamboyant and powerful personality attracted her to him instantly. Their shared love for the stage could also have played an important factor in their mutual attraction.

In 1899, at the turn of the century, they set out with a theater troupe for San Francisco, where Yakko was promoted as the starlet of the troupe. She was given the stage name “Sadayakko” and debuted on May 25th. Her dance was bewitching and so skillful that she ignited a storm of applause.

Sada Yakko circa 1910s

Her dance wowed audiences immediately and her debut was a great success. She became an icon—the entrancing Yakko, the most celebrated geisha in Japan and a woman who bewitched Westerners without the ability to speak a word of their language.

Their first tour was across the United States from June 1899 to April 1900. It crossed the Atlantic and continued on to Europe from May 1900 to November 1901. They departed for their second tour in April 1901 and toured around Europe until July 1902.

Once arriving in America, Sada Yakko and her troupe quickly found success. After winning the respect and recognition of superstar Isadora Duncan, another celebrity, American Loïe Fuller elevated her status even further. Thanks to him, the doors of the theatre in Paris were opened to her, and he even acted as an interpreter in her interviews with foreign magazines. In 1900, Sada Yakko performed The Geisha and the Knight in Paris as part of the Exposition Universelle and became an overnight success. It was the first time that a Japanese theatre troupe had appeared in France, and they were so triumphant that Sada Yakko was even invited to host a garden party at the Élysée Palace—the official residence of the French president.

Sada Yakko as Musume Dojoji, 1907

Her success continued the entire time she was abroad. Pablo Picasso sketched her; Debussy was inspired by her when composing music. Her arrival in Paris coincided with the Japonisme movement, which she contributed to as an idol and muse for French creatives. Guerlain created a perfume in her honor named “Yacco.”

Sketch of Sada Yakko by Picasso

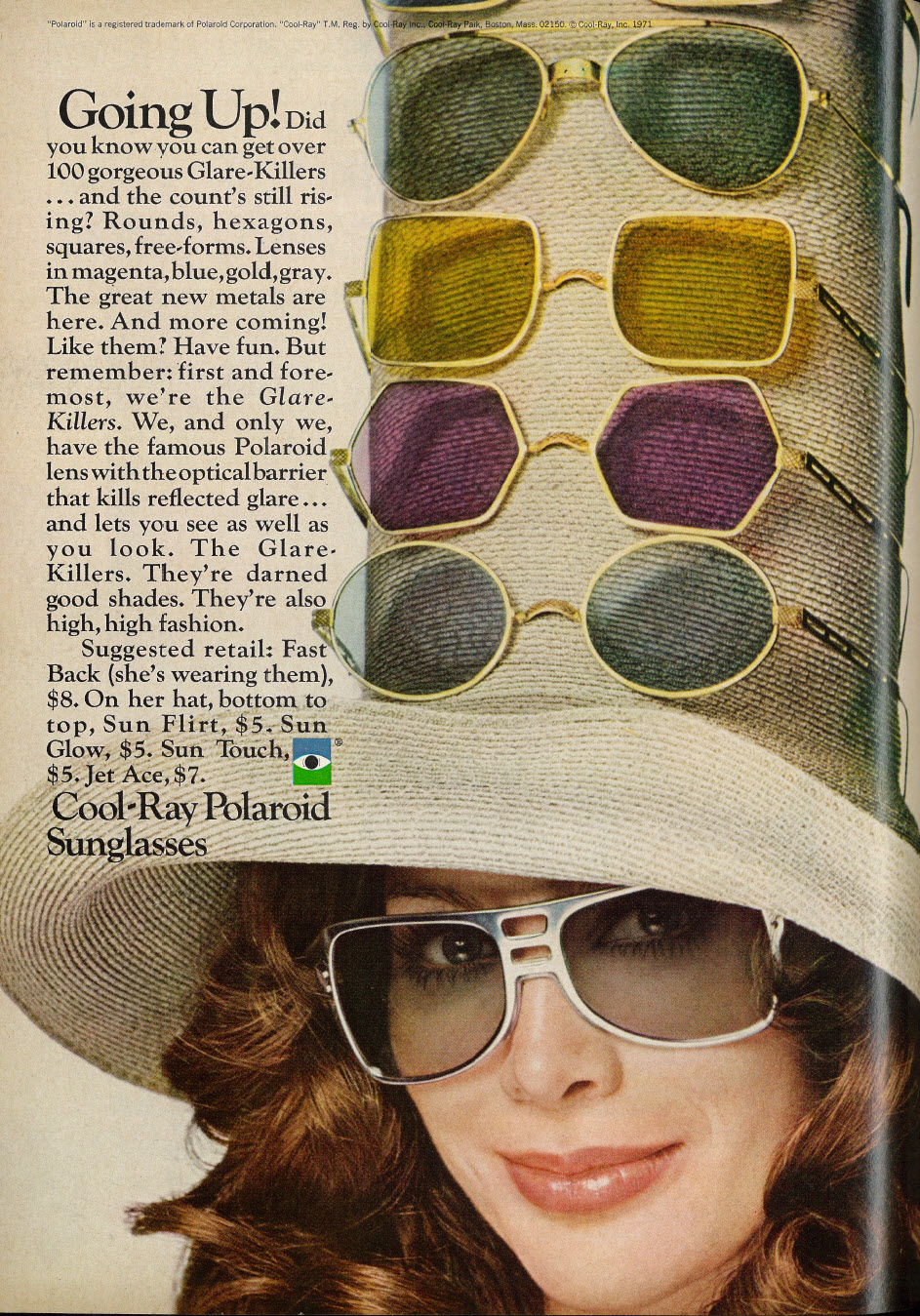

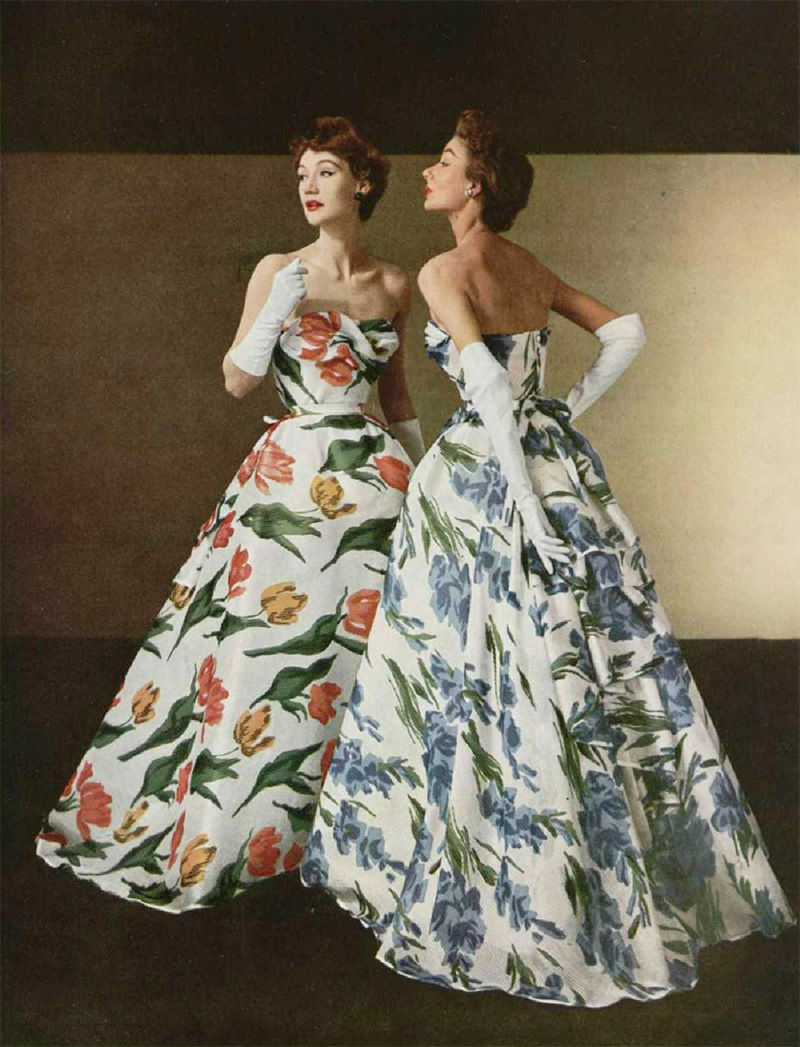

An interest in kimono accompanied the sweeping wave of Japonisme, and Sada Yacco became the face of it in Paris. An elegant shop called Au Mikado bought the right to use “Yacco” as a brand name. Here, they sold the “Yacco” Guerlain perfume, “Yacco” skin cream, and even “Yacco” candy. But the most popular item was the “Kimono Sada Yacco.” Before the release of Au Mikado’s “Kimono Sada Yacco,” the only women who could afford (Westernized) kimono were the wealthy because of its lavish expense. However, with the introduction of “Kimono Sada Yacco,” ordinary women could afford the look too. The garments sold for a mere 12 to 18 francs. Now everyone could enjoy the exotic lifestyle of Sada Yakko!

An advertisement for “Kimono Sada Yacco”

After returning home to Japan from Paris, Yakko opened her own acting school for women in Tokyo. Applicants were to be aged between 16 and 25, educated to at least the junior high school level, and have two guarantors who were Tokyo homeowners. They were to be educated in history, script writing, traditional and modern acting skills, Japanese and Western dancing, and musical instruments such as the flute, shoulder drum, shamisen, and koto. The course would be two years and wouldn’t cost a yen, but students were expected to perform at the Imperial Theater as part of their practical training. Anyone who left before the two years were up would be charged for the tuition costs that had been waived. Out of 100 applicants, Yakko selected 15 students, and the school opened on September 15, 1908.

Less than a year after Otojiro’s death, perhaps around April 1912, Yakko rekindled her relationship with the married businessman, Momosuke Fukuzawa. They had known each other since childhood and were both in need of some love and support. Although it was not uncommon for married men to seek out mistresses, it was typically done in secret. This, however, was not the case with Yakko and Momosuke. They lived together, traveled together, and flirted with each other so openly that they caused a public scandal. Despite the critics, they both continued to support each other’s careers—Yakko was now starring in acting roles of her own choosing and Momosuke was pursuing several business ventures.

In September 1917, Sadayakko announced her retirement, with her last performance being the lead in the opera, Aida. When Sada retired, she gave up her stage name and geisha name. In 1933, Momosuke was in poor health and they decided that he should move back to his house and wife in Shibuya, and they ended their relationship. They held a solemn ceremony to mark the end—they’d been together for over 20 years. She survived the war, but soon after Japan surrendered, Sada discovered that she had cancer of the liver, which had spread to her throat and tongue. She died on December 7, 1946 at the age of 75.

Sada Yacco was a pioneer of her time, her culture, and her gender. She influenced an entire fashion movement in Paris, and traces of that influence remain today in the form of contemporary Western fashion companies selling “kimono” that resemble more of a duster or long open cardigan. The remaining kimono-inspired fashion of contemporary time is Sada’s cyclicity.

Sada Yakko reading

Sources: “Sada Yacco”; “The Story of Sada Yacco, the Japanese Geisha who Bewitched Europe”; “How Japan’s Most Prominent Geisha Was The Original Beauty Influencer”